Optimizing Handwriting

How long have you been hand-writing for? Ever stopped to wonder if you could be doing it better?

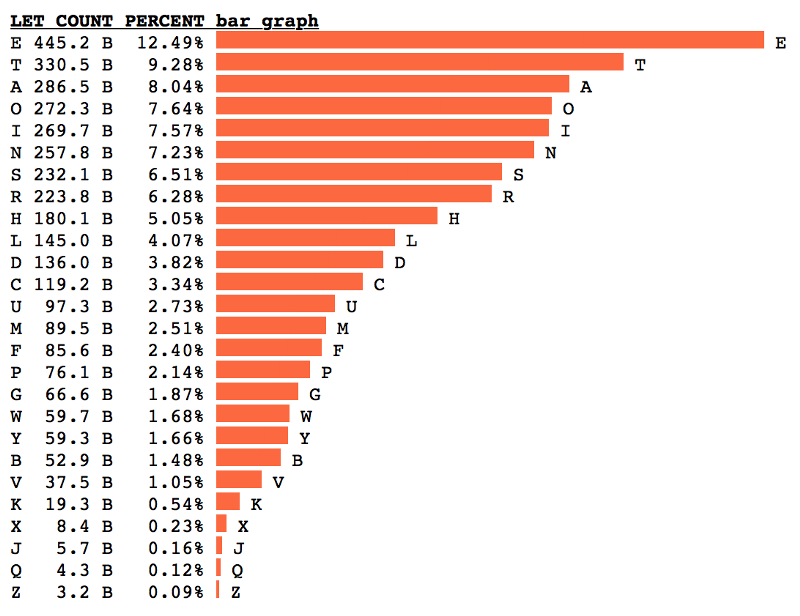

While journaling, I noticed that the faster I write, the less legible my “e” becomes. This is the most common letter in the whole language, right?

Yes, “e” is the most common letter in English. If the most common letter is difficult to write, something is wrong.

Frequently-used letters should be easier to write than infrequently-used letters.

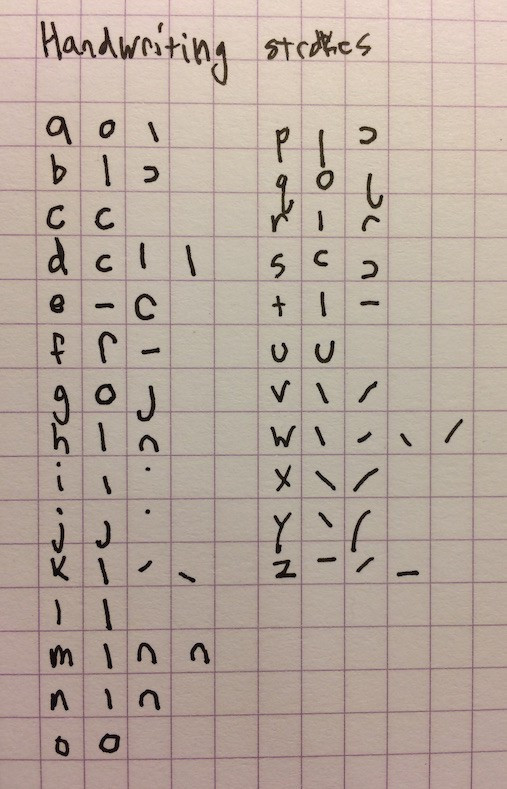

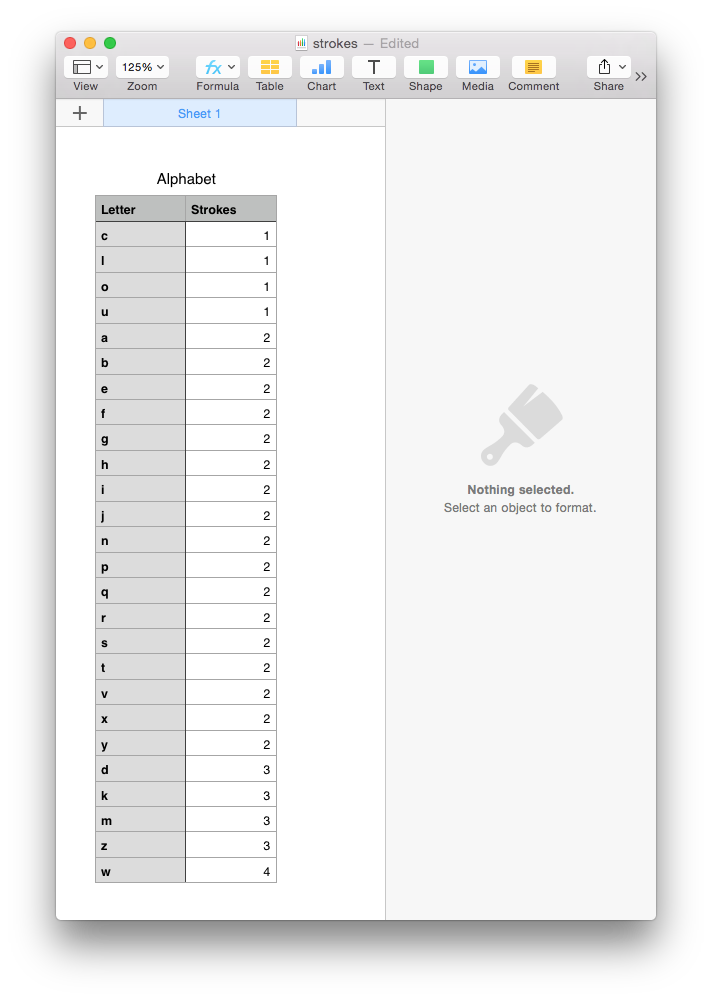

To quantify difficulty, I charted how many “strokes” it takes me to write each letter.

I counted the number of strokes for each letter, and sorted by stroke count.

Looking back at Peter Norvig’s letter frequency chart, of the 4 letters which take a single stroke to write, “o” is the only one that appears in the top-4 most-frequent characters.

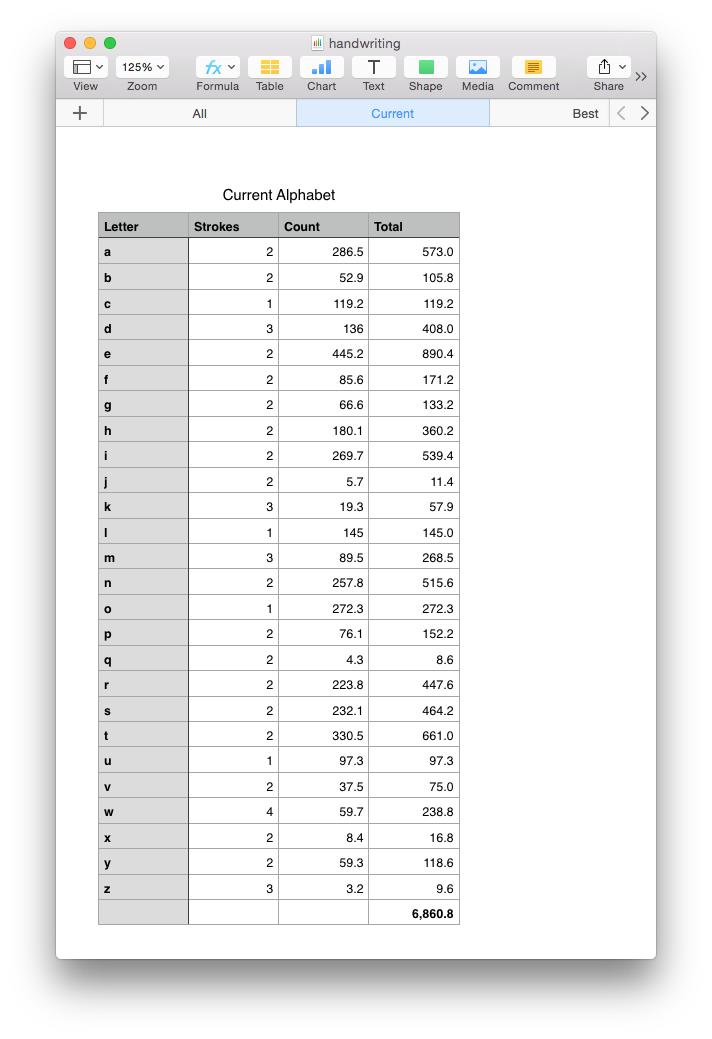

To measure how well the entire alphabet is suited to actual usage, I counted the number of strokes it would take to hand-write every letter in Peter Norvig’s text corpus.

For our current alphabet, that would be just shy of 7 trillion strokes.

Could it be better? Yes. The simplest change would be to re-assign letters that are already in our alphabet. For example, to swap “e” and “l”, so that the word “hello” would be written “hleeo”. This looks weird, but we’d get used to it. The result would be that the most-frequently used letter is also the easiest to write.

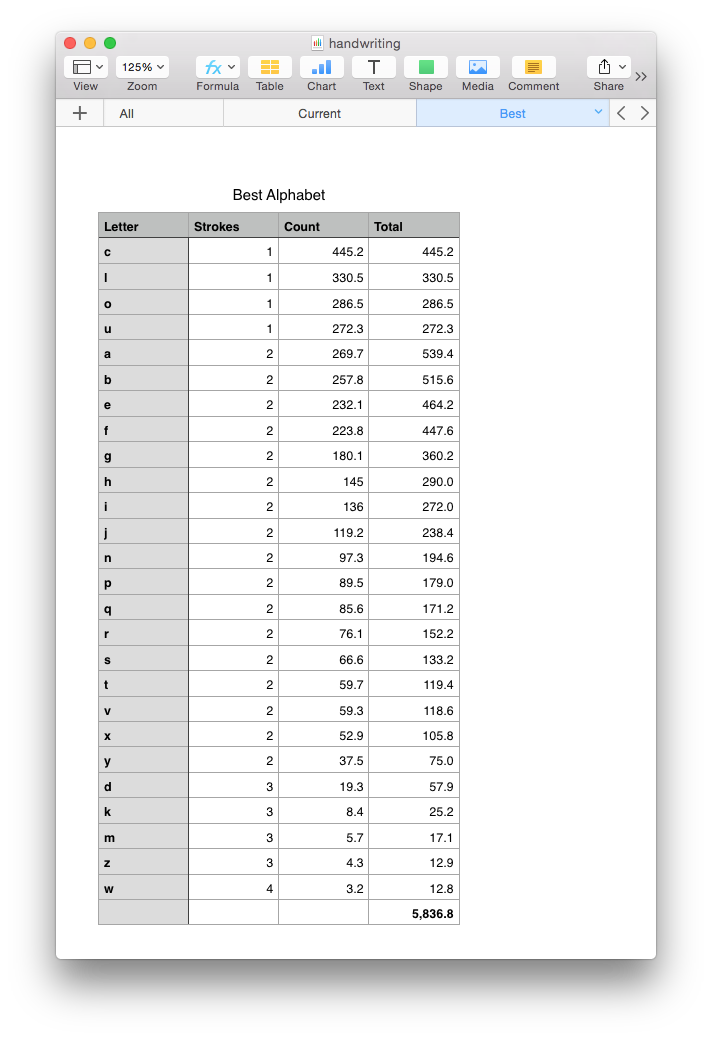

Pairing the new-letters with fewest strokes with old-letters with highest frequency, yields the following spreadsheet.

This has a total stroke count of a trillion fewer than the current alphabet system that we use. That is an efficiency boost of 15%.

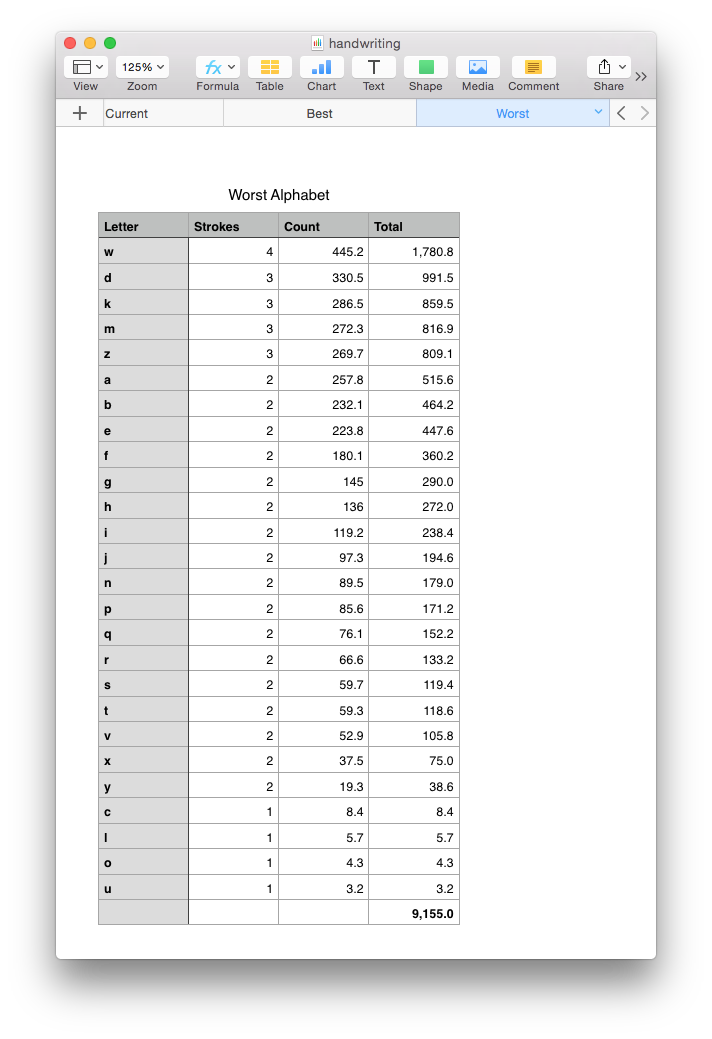

To put things in perspective, let’s see how bad it could be.

The worst-case alphabet would make the most-frequent letters the hardest to write. This system would take over 9 trillion strokes. That is 33% worse than what we have now.

To put it another way, our current alphabet is 69% of the way from worst to best. It could have been worse, but there is tremendous potential for a new alphabet to get thoughts to paper more efficiently.